From the Field – Agronomy Notes

go.ncsu.edu/readext?519990

en Español / em Português

El inglés es el idioma de control de esta página. En la medida en que haya algún conflicto entre la traducción al inglés y la traducción, el inglés prevalece.

Al hacer clic en el enlace de traducción se activa un servicio de traducción gratuito para convertir la página al español. Al igual que con cualquier traducción por Internet, la conversión no es sensible al contexto y puede que no traduzca el texto en su significado original. NC State Extension no garantiza la exactitud del texto traducido. Por favor, tenga en cuenta que algunas aplicaciones y/o servicios pueden no funcionar como se espera cuando se traducen.

Português

Inglês é o idioma de controle desta página. Na medida que haja algum conflito entre o texto original em Inglês e a tradução, o Inglês prevalece.

Ao clicar no link de tradução, um serviço gratuito de tradução será ativado para converter a página para o Português. Como em qualquer tradução pela internet, a conversão não é sensivel ao contexto e pode não ocorrer a tradução para o significado orginal. O serviço de Extensão da Carolina do Norte (NC State Extension) não garante a exatidão do texto traduzido. Por favor, observe que algumas funções ou serviços podem não funcionar como esperado após a tradução.

English

English is the controlling language of this page. To the extent there is any conflict between the English text and the translation, English controls.

Clicking on the translation link activates a free translation service to convert the page to Spanish. As with any Internet translation, the conversion is not context-sensitive and may not translate the text to its original meaning. NC State Extension does not guarantee the accuracy of the translated text. Please note that some applications and/or services may not function as expected when translated.

Collapse ▲M.J. Mulvaney1, P. Cockson3, B. Whipker3, C. Crozier2, R. Seepaul4, I. Small4, D. Wright4, S. Paula-Moraes1, A. Post5, and R. Leon5

1 University of Florida, IFAS, West Florida Research and Education Center, Jay, FL

2 North Carolina State University, Vernon G. James Research and Extension Center, Plymouth, NC

3 North Carolina State University, Horticultural Science Dept., Raleigh, NC

4 University of Florida, IFAS, North Florida Research and Education Center, Quincy, FL

5 North Carolina State University, Crop and Soil Sciences Dept., Raleigh, NC

Identification of Carinata Frost Damage Grown in the Southeastern US

Brassica carinata, sometimes called “Ethiopian mustard,” “Abyssinian mustard,” or simply “carinata,” is an annual oilseed crop used for the commercial production of jet fuel. Carinata by-products include seed meal for animal feed (Agrisoma, 2017) and residue may act as a bio-suppressant against nematodes (Oka, 2010). It is similar in growth habit to canola. It is grown during the winter in the southeastern United States and shows potential as an alternative winter crop for the region.

One of the challenges to commercialization of this crop in the region has been frost damage. Since the crop is planted in the late Fall, temperatures can sometimes fluctuate between 50°F (10°C) during the day to 20°F (-6.7°C) that same night, giving the crop little time to harden off. Susceptibility to frost damage depends on temperature, duration at a given temperature, and crop growth stage. Genotype screening trials throughout the Southeast are underway to identify more frost-tolerant cultivars.

This document serves as a guide to identify levels of frost damage as well as management issues related to frost damage of carinata in the Southeast. Be aware that this is a new crop to the Southeast and research on this topic continues. This publication represents the latest information available and will be updated over time as new research knowledge is gained.

Symptomology

The severity of frost damage injury depends on the crop stage. At the seedling stage, when roots are shallow and there are no carbohydrate reserves, frost can kill the crop. At the rosette stage, leaves protect the growing point and roots are deeper, resulting in greater frost tolerance, although leaf tissue injury can occur. After bolting, the stalk and growing points are most susceptible to frost damage. Stalk damage typically results in tissue damage several inches above the soil surface, where structural bending stresses are high. Growing point death will result in new shoot growth from the crown of the plant.

Minor frost damage first appears as wilting of the leaves, and within 10 days manifests as bleaching of the leaves, particularly near the tips and leaf margins (Figure 1). If frost damage is more severe, these areas will become necrotic (brown), but plants will recover from this level of damage (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Leaf bleaching typically evident 1-2 weeks after a freeze event in carinata. The crop will outgrow this type of injury. UF/IFAS West Florida Research and Education Center, Jay, FL. Photos: M.J. Mulvaney

Cumulative hours below temperature thresholds four weeks prior to the date the photos were taken.

| Planted: | 2-Nov-2017 |

| Photo taken: | 20-Dec-2017 |

| Temperature | Cum. hrs. below |

| 32°F (0°C) | 30.5 |

| 25°F (-3.9°C) | 0.0 |

| 20°F (-6.7°C) | 0.0 |

| 15°F (-9.4°C) | 0.0 |

Figure 2. Tissue affected by cold injury may become necrotic. The crop will outgrow this level of injury. UF/IFAS West Florida Research and Education Center, Jay, FL. Photo: M.J. Mulvaney

Cumulative hours below temperature thresholds four weeks prior to the date the photo was taken.

| Planted: | 23-Nov-2015 |

| Photo taken: | 8-Jan-2016 |

| Temperature | Cum. hrs. below |

| 32°F (0°C) | 10.3 |

| 25°F (-3.9°C) | 0.0 |

| 20°F (-6.7°C) | 0.0 |

| 15°F (-9.4°C) | 0.0 |

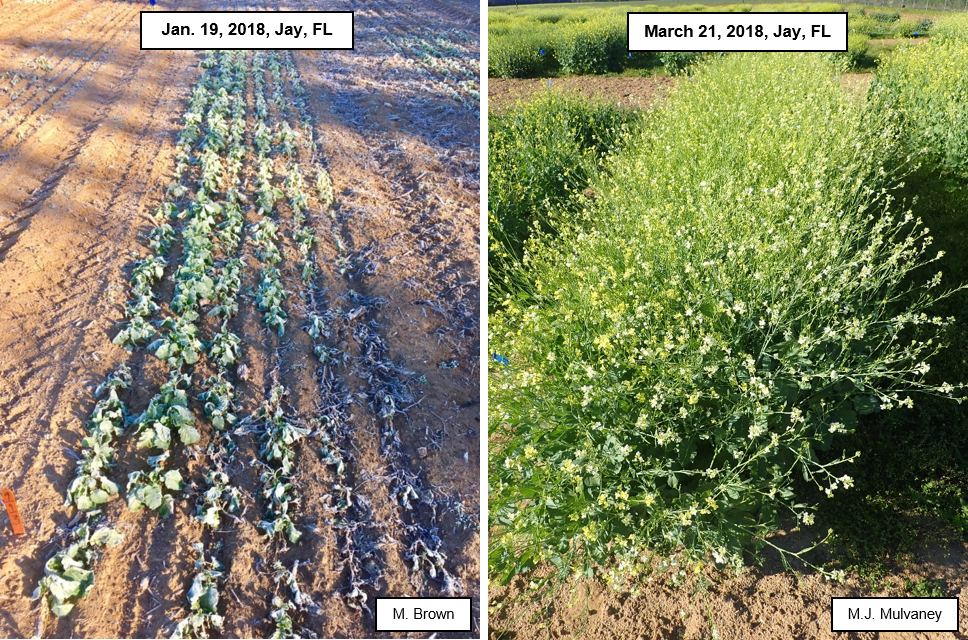

Severe cold damage is shown in Figure 3. This level of injury is expected to reduce stands and yield. Note that above-ground tissue is severely affected, but the roots did not die. The plants in Figure 3 grew back from the growing point, but may have also re-sprouted at the crown if the roots did not freeze. Re-planting of this field is not recommended due to lateness and because the crop will continue to produce.

Figure 3. More severe cold damage of carinata during early bolting. This level of injury is expected to reduce stands and yield. Note that above-ground tissue is severely affected, but neither the growing points nor roots died. This field generally grew back from the growing point, but could have re-sprouted at the crown if the damage was more severe. UF/IFAS West Florida Research and Education Center, Jay, FL. Photo: M.J. Mulvaney

Cumulative hours below temperature thresholds four weeks prior to the date the photo was taken.

| Planted: | 2-Nov-2017 |

| Photo taken: | 19-Jan-2018 |

| Temperature | Cum. hrs. below |

| 32°F (0°C) | 196.8 |

| 25°F (-3.9°C) | 63.8 |

| 20°F (-6.7°C) | 14.5 |

| 15°F (-9.4°C) | 0.0 |

After bolting, frost injury of the stalk can be more problematic (Figure 4). Splitting of the stem may be evident between the soil surface and several inches off the ground, but the stalk can freeze without splitting, effectively killing the vascular tissue which results in a wilted appearance. When this happens, the stem can hollow out at the point of damage. The weakened stem often results in lodging, though the crop will often ‘right’ itself, giving a “J-stemmed” appearance (Figure 5). The injured stem can serve as an entry point for pests, such as Sclerotinia (leading to Sclerotinia stem rot) and yellow margined leaf beetles (Microtheca ochroloma Stål) (Figure 6).

Figure 4. Left) severe frost damage of carinata in Quincy, FL. Note growing point damage on the left and lodging on the right. This crop will re-grow from the crown at an approximated 70% yield penalty. Re-planting after January 15 may be expected to incur at least 50% yield penalty. UF/IFAS North Florida Research and Education Center, Quincy, FL. Photo: R. Seepaul. Right) Recovery and re-growth after lodging caused by stem weakening during frost. UF/IFAS West Florida Research and Education Center, Jay, FL. Photo: M.J. Mulvaney

Cumulative hours below temperature thresholds four weeks prior to the date the top photo was taken.

| Photo taken: | 15-Jan-2014 |

| Temperature | Cum. hrs. below |

| 32°F (0°C) | 61.8 |

| 25°F (-3.9°C) | 19.3 |

| 20°F (-6.7°C) | 3.5 |

| 15°F (-9.4°C) | 0.0 |

Figure 5. Freeze damage at bolting can cause stem injury, including splitting and/or hollowing of the stem, typically within several inches of the soil surface. Lodging often results, but the plant may continue to grow. In severe cases, re-growth will occur at the crown. UF/IFAS West Florida Research and Education Center, Jay, FL. Photos: M.J. Mulvaney (top), P.L. Phillips (bottom)

Figure 6. Stalk damage due to frost can lead to pest infestation, such as yellow margined leaf beetle larvae (A & B), Sclerotinia stem rot (C), and/or stem breakage (A & D). UF/IFAS West Florida Research and Education Center, Jay, FL. Photos: M.J. Mulvaney.

| Planted: | 16-Nov-2017 |

| Photo taken: | 19-Jan-2018 |

| Temperature |

Cum. hrs. below |

| 32°F (0°C) |

196.8 |

| 25°F (-3.9°C) |

63.8 |

| 20°F (-6.7°C) |

14.5 |

| 15°F (-9.4°C) |

0.0 |

Frost injury during pod-fill is problematic due to poor seed set and pod abortion. This may cause undeveloped seeds and empty pods leading to severe yield loss. A crop that has suffered frost damage during pod-fill may re-sprout from the crown. A field suffering this level of damage can be considered a complete loss.

While frost damage can be severe, carinata has shown impressive resiliency. Growers in NW Florida jokingly call this ‘the Lazarus crop’ because of its ability to apparently come back from the dead. The same plot after a hard frost is shown in Figure 7, where about 25% of the plants suffered mortality. Carinata can promote branching to ‘compensate’ for stand loss, but there is some evidence that secondary branches may not be as productive as primary branches.

Figure 7. The same carinata genotype shown after a hard frost (left) and during flowering (right). This plot suffered approximately 25% mortality. Note that increased branching can fill in the gaps, although secondary branches may not be as productive as primary branches. UF/IFAS West Florida Research and Education Center, Jay, FL. Photos: M. Brown (left), M.J. Mulvaney (right)

Be advised that this is a relatively new crop to the Southeast. Ongoing research will change production recommendations as new information is generated. Additionally, promising new carinata varieties with improved frost tolerance and yield gains derived from the breeding program are being developed to fit the expansion of the southern tier commercial production area (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Frost tolerant carinata lines derived through breeding indicate that promising varieties for tolerating hard freeze events will be available to the region in the near future. Photo: Agrisoma

How to minimize risk of frost injury to carinata

- A general recommendation is that carinata should be sown approximately six weeks before first frost.

- In North Carolina, planting should occur between mid-September to early October. In the Florida panhandle, plant in the first two weeks of November. Earlier plantings will reduce yield, and later plantings are more likely to result in small plants at the seedling stage with shallow roots during freezes. Plants at this stage are more susceptible to frost damage and may require re-planting if the roots freeze. Timely planting allows plants to develop into the rosette stage, when frost tolerance is greater, during the times of greatest probability of frost.

- Do not over-apply early-season nitrogen. Excessive nitrogen will promote luxuriant growth that is more susceptible to frost damage. Limit at-plant nitrogen applications to 20 lbs N/acre or less. Be sure to calibrate your spreader so that you don’t over-apply. Topdress N applications are typically made between bolting and flowering.

References

Agrisoma. 2017. Carinata Management Handbook, Southeastern US 2017-18. Agrisoma USA, Tifton, GA.

Oka, Y. 2010. Mechanisms of nematode suppression by organic soil amendments—A review. Applied Soil Ecology 44: 101-115. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2009.11.003.

Funding and Acknowledgments:

Funding for this work/study was received through USDA-NIFA Bioenergy Coordinated Agricultural Project (CAP). This material is based upon work that is supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture under award number 2017-68005-26807. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Suggested Citation:

M.J. Mulvaney1, P. Cockson3, B. Whipker3, C. Crozier2, R. Seepaul4, I. Small4, D. Wright4, S. Paula-Moraes1, A. Post5, and R. Leon5 2018. Identification of carinata frost damage grown in the Southeastern US. North Carolina St. Univ. Small Grains Portal – From the Field-Agronomy Notes.

1 University of Florida, IFAS, West Florida Research and Education Center, Jay, FL

2 North Carolina State University, Vernon G. James Research and Extension Center, Plymouth, NC

3 North Carolina State University, Horticultural Science Dept., Raleigh, NC

4 University of Florida, IFAS, North Florida Research and Education Center, Quincy, FL

5 North Carolina State University, Crop and Soil Sciences Dept., Raleigh, NC